In countless primary health care settings across low- and middle-income countries, the daily reality for frontline workers is one of overwhelming administrative toil, where the process of collecting data becomes a greater focus than the patient care it is meant to support. These dedicated professionals are often buried under a mountain of manual, paper-based forms that are duplicative, fragmented, and excessively time-consuming, transforming what should be a source of valuable insight into a significant professional burden. This systemic inefficiency leads to a cascade of negative consequences, including poor-quality information, widespread burnout, and a fundamental undermining of the health system’s ability to make strategic, data-driven decisions. The result is a reactive cycle of bureaucratic reporting that traps health systems, preventing them from leveraging data as the powerful strategic asset it has the potential to become.

The Paradox of Digital Transformation

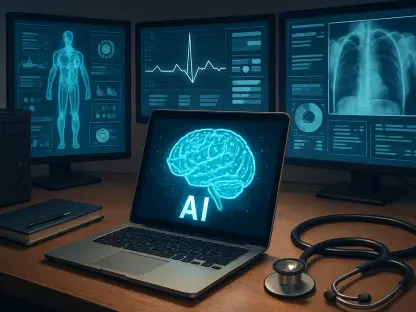

The global movement toward the digitalization of health data systems represents a clear and substantial opportunity to reverse this trend by significantly reducing the manual processing burden on health workers. Digital tools promise to eliminate the physical constraints of paper, such as supply shortages and storage issues, while generating real-time data visibility that empowers health managers to make timely, responsive decisions about resource allocation and public health interventions. This transition is not merely an upgrade; it is a fundamental reimagining of how information can flow through a health system to improve efficiency and outcomes. By automating routine tasks and providing immediate access to clean, aggregated data, digitalization has the potential to free up valuable time for patient care and enable a more proactive, evidence-based approach to managing community health, making it an essential objective for modern health care reform.

However, the journey to a fully digital, nationwide health information system is a lengthy and complex marathon, not a sprint, and for most health facilities, a hybrid model where digital and paper-based systems coexist is the operational reality. This extended transition period, particularly in rural and under-resourced settings, is often viewed as a temporary problem to be endured rather than a strategic phase to be managed. A more effective approach reframes this interim period as a critical opportunity for intentional planning, gradual capacity building, and the deployment of targeted solutions that can provide immediate value. Acknowledging the hybrid reality allows for the development of national roadmaps that explicitly plan for this phase, integrating pragmatic innovations that can accelerate progress and reduce the burden on the workforce at every stage of the scale-up process, thereby paving the way for a more successful and sustainable full-scale digital system in the future.

Building a Foundation for Success

Perhaps the most emphatic finding in the pursuit of stronger health data systems is that technology, no matter how advanced, cannot fix a broken process. Innovation will almost certainly fail if it is layered on top of a weak or dysfunctional foundation, a phenomenon that has been observed repeatedly in various global health initiatives. Before countries make significant investments in new digital solutions, they must first review and strengthen the core components of their primary health care data value chain. A common problem is the existence of multiple, overlapping reporting tools from different programs or donors, forcing health workers to enter the same data repeatedly. This is often compounded by unclear roles and responsibilities, where data collection and verification tasks are not formally defined or allocated sufficient time. Furthermore, many systems utilize performance-based incentives that, while well-intentioned, can inadvertently encourage the falsification or manipulation of data to meet targets, further eroding the integrity of the system.

Addressing these foundational weaknesses is universally applicable across all levels of digital maturity and often yields a greater and more sustainable impact than the introduction of new technologies alone. The solutions are typically less costly and focus on fundamental process improvements. This involves a concerted effort to streamline, harmonize, and standardize reporting requirements, focusing only on collecting essential data that will be actively used for decision-making. It also requires formally defining who is responsible for data collection, entry, verification, and analysis, and protecting time for these tasks within their job descriptions. Critically, incentive structures must be reformed to reward data accuracy, completeness, and quality over sheer quantity or the achievement of unrealistic targets. These foundational improvements create the stable, enabling environment that is a non-negotiable prerequisite for any technological innovation to succeed and deliver its intended value.

A Pragmatic Approach to Innovation

Many health systems have been subjected to waves of donor-funded pilot projects that generate initial excitement but ultimately fail to scale or be sustained once external funding disappears, a cycle often referred to as “pilotitis.” This history has cultivated a healthy skepticism toward new innovations and underscores the need for a more disciplined and balanced approach. Strong governance, robust infrastructure, and clear technical and data standards should not be viewed as barriers to innovation but as the essential prerequisites for its sustainable implementation. This requires health leaders to be highly selective about which innovations to pursue, focusing on those that offer a genuine opportunity to leapfrog traditional constraints or solve problems for which no conventional solution exists. It is a strategic shift from chasing novelty to prioritizing scalable, long-term impact through deliberate planning and governance.

Concurrently, it is equally important to be honest about problems that do not require an innovative fix but rather straightforward resource allocation and better management. For instance, a chronic shortage of paper-based reporting forms is fundamentally a procurement and supply chain problem that needs a better printing and distribution plan, not a new software application. Likewise, a lack of devices is a procurement challenge that may be addressed with a sustainable purchasing strategy or a bring-your-own-device (BYOD) policy, not another small-scale pilot project. Pragmatic interim solutions can also bridge critical gaps during the transition; for example, solar-powered solutions can provide reliable electricity for digital devices in off-grid locations, and simple, non-digital tools like color-coded kanban stock cards can vastly improve inventory management. The central message is to prioritize the deliberate and sustainable scaling of proven approaches while being judicious in the adoption of new ones.

A Roadmap for a Data-Driven Future

The successful transformation of a primary health care data system from a debilitating administrative burden into a dynamic, strategic asset was not the result of a singular technological leap. Instead, it was a carefully orchestrated journey that honored the current realities of health systems while systematically building towards a more robust and data-driven future. The path forward required a holistic framework built on three interconnected pillars. The first was strategic planning, which involved developing national roadmaps that explicitly accounted for the hybrid transition period and integrated pragmatic, interim solutions to provide immediate relief and build momentum. The second pillar was an unwavering attention to fundamentals, prioritizing the strengthening of foundational systems—including clear roles, streamlined processes, and sensible incentives—as the essential bedrock of any successful reform.

Finally, the journey necessitated a balanced approach to innovation. This involved selectively adopting new technologies that solved unique problems while focusing primarily on sustainably scaling proven solutions. As countries moved forward, continued evaluation became essential. Implementation research was integrated into digitalization plans from the outset to generate localized data on effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and user experience, which guided ongoing refinement and scale-up decisions. By embracing this comprehensive and pragmatic framework, health systems methodically transformed their primary health care data, unlocking its full potential to drive better health outcomes for the communities they served.