A diagnostic imaging machine, having faithfully served a decade in a European hospital, now presents a complex quandary for Indiis it a cost-effective tool for expanding healthcare to underserved communities or a potential danger to patient safety that undermines domestic industry? This dilemma sits at the heart of a fierce debate ignited by a potential government policy shift that has fractured the nation’s health technology sector. The central question facing hospitals, regulators, and manufacturers is whether a pre-owned MRI machine represents a second-hand lifesaver or a first-class risk.

A Second-Hand Lifesaver or a First-Class Risk

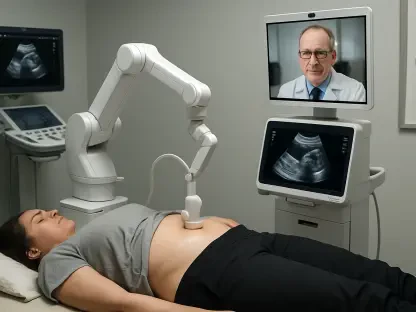

The debate over refurbished medical equipment is not merely academic; it is a tangible issue playing out in clinics and hospitals across the country, particularly outside the major metropolitan hubs. For a small diagnostic center in a Tier-2 city, the choice between a new, multi-crore CT scanner and a certified, pre-owned model at a fraction of the price can determine whether it can offer advanced diagnostic services at all. Proponents argue that these devices bridge a critical accessibility gap, bringing modern medicine to populations that would otherwise be left behind.

However, this argument for affordability is met with stark warnings about safety and performance. Critics question the reliability of aging technology, the transparency of its maintenance history, and the potential for misdiagnosis due to degraded performance. The issue forces a difficult conversation about acceptable levels of risk and whether the economic benefits of using pre-owned equipment justify the potential compromise in clinical outcomes. This core conflict—access versus safety—fuels the ongoing policy battle.

A Policy Vacuum Creates a Divided Industry

Responding to years of regulatory ambiguity, the Union Health Ministry has stepped into the fray by establishing a committee to formulate a clear policy for regulating refurbished high-end medical devices. This move challenges a long-standing, if informal, import ban and has transformed a simmering industry disagreement into a full-blown policy battleground. The committee’s mandate is to create a formal framework where none currently exists, forcing stakeholders to confront the issue directly.

The stakes of this debate are substantial, revolving around a contentious market estimated at 10% of India’s total medical device sector, which is projected to be worth over Rs 76,000 crore by 2028. These pre-owned devices are disproportionately concentrated in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, where the pressures of affordability and access are most acute. The government’s decision will therefore have a significant impact not only on the industry’s economic landscape but also on the quality and availability of healthcare for millions of citizens.

The Two Sides of the Scalpel a Clash of Interests

Championing the cause against imports is the Association of Indian Medical Device Industry (AiMeD), which represents domestic manufacturers. The organization has raised significant red flags over both safety and economic sovereignty, arguing that allowing refurbished imports without a regulatory framework benchmarked against global standards presents an “unacceptable clinical risk.” This position is rooted in the belief that patient well-being must remain the paramount consideration, above all economic arguments.

Beyond safety, AiMeD frames the issue as a direct threat to national initiatives like “Make in India.” The fear is that an influx of cheaper, used equipment will stifle local innovation and relegate India to a “dumping ground for end-of-life equipment,” preventing its domestic industry from ascending the value chain. Compounding these concerns is the existence of a shadow market, with an estimated Rs 12,000-15,000 crore in unregulated trade of pre-owned equipment already operating without any oversight, posing immediate risks.

In sharp contrast, the Medical Technology Association of India (MTaI), representing multinational corporations, has welcomed the government’s move. MTaI envisions a strategic advantage, proposing that a well-regulated market could position India as a “premier electronics repair hub for the Global South.” This vision aligns with the government’s broader Electronics Repair Services Outsourcing (ESRO) initiative, suggesting a path toward economic growth and job creation. Moreover, MTaI contends that affordable, refurbished equipment can lower procurement costs for healthcare facilities, ultimately making advanced diagnostics and treatments more accessible in smaller cities and towns.

Voices from the Field Expert Opinions and Legal Challenges

The debate is enriched by voices from clinical practice who stress the real-world implications. Dr. Sudhir Srivastav, CEO of SS Innovations, offers a surgeon’s warning, emphasizing the critical dangers of using older technology in high-stakes equipment like surgical robots. In procedures where micrometer precision is the difference between success and failure, the performance of refurbished parts or systems introduces a variable that many clinicians find unacceptable.

Adding to the complexity is the legal and ethical landscape. Rajiv Nath of AiMeD has questioned the lack of transparency in the current system, noting that hospitals rarely disclose the age of their equipment, and any cost savings from using older devices are seldom passed on to patients. This opacity was underscored by a 2024 Delhi High Court ruling, which dismissed a Public Interest Litigation from a patient advocacy group. The court’s decision highlighted the complete absence of any legal provisions permitting refurbished imports, thereby reinforcing the urgent need for a clear and enforceable policy to fill the legal void.

Charting a Course Through Policy Hurdles and Global Roadmaps

The newly formed government committee faces a critical and complex mandate. Its first task is to create a precise definition for “refurbished medical devices” to distinguish them from simply used or repaired equipment. Subsequently, it must develop a robust methodology to evaluate the safety, performance, and remaining lifespan of this equipment and establish clear guidelines for its eventual disposal and waste management to prevent environmental hazards.

This policy initiative follows a period of regulatory confusion. In 2023, the environmental ministry briefly permitted imports under an e-waste management framework, only to be overruled by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), which reiterated that no such imports were legally permitted. This history of policy whiplash underscores the need for a unified and stable regulatory approach. As India charts its course, it can draw lessons from highly regulated markets like the United States and the European Union, where pre-owned medical equipment is safely managed. These international examples demonstrated that a functional market was possible, but its success hinged entirely on the creation and strict enforcement of a robust regulatory framework—the very element that remained at the center of India’s contentious debate.