With a deep passion for leveraging technology to advance healthcare, James Maitland stands at the intersection of robotics, IoT, and medicine. Today, he joins us to dissect a seismic proposal from the Department ofHealth and Human Services’ technology office, a rule that aims to fundamentally reset the landscape of health IT policy. We’ll explore the thinking behind this dramatic deregulatory shift, which promises to gut nearly 70% of existing certification requirements. Our conversation will delve into the proposed new foundation for artificial intelligence in healthcare, the controversial removal of long-standing security and transparency mandates, and what these changes could mean for innovation, patient safety, and the future of data exchange.

The new rule proposes altering nearly 70% of requirements, stating they hinder developer innovation. Can you provide a concrete example of how a specific certification requirement has slowed a product launch, and what metrics developers use to measure this regulatory friction?

Absolutely. While the proposal doesn’t name specific products, you can easily imagine the friction. Think about a startup developing a cutting-edge patient portal. Under the current rules, they have to engineer to a long checklist that includes mandates like “safety-enhanced design” and “accessibility-centered design.” Building and documenting compliance for each of these prescriptive features adds months, sometimes years, to a development cycle. It’s not just coding time; it’s the exhaustive testing, documentation, and certification process that creates a massive drag. Developers measure this friction in terms of “time-to-market” and the sheer cost of engineering hours dedicated not to core innovation, but to satisfying a regulatory line item that they believe the market would demand anyway. This proposal essentially argues that the market, not a government checklist, should drive these features.

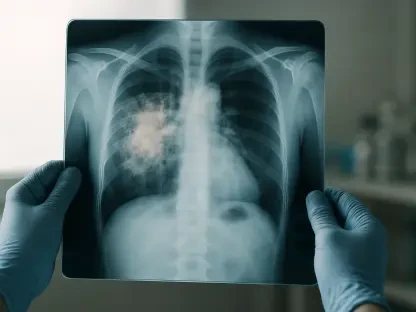

The proposal aims to create a “new foundation” for AI through FHIR APIs. Can you describe step-by-step what this new foundation entails and give an example of an AI-enabled solution, currently impractical due to regulations, that this change would make possible?

The “new foundation” is less a step-by-step construction project and more like clearing a cluttered lot to build something new. First, they are removing the old, rigid requirements that dictate how systems must be built. Second, in that cleared space, they are elevating FHIR APIs as the primary, flexible standard for data exchange. This creates an environment where developers aren’t just building to pass a test but are creating “creative AI-enabled interoperability solutions.” A powerful example enabled by this change would be an autonomous AI monitoring system for chronic disease. Right now, rules around “access” and “use” can be restrictive. With the proposed changes, an AI could be authorized to proactively and continuously pull data from a patient’s EHR, their pharmacy records, and even their home monitoring devices, then share a synthesized risk score directly with a specialist’s system—all without a specific, manual query from a human. It’s a shift from reactive data pulling to proactive, autonomous data exchange.

The rule proposes removing requirements like multi-factor authentication and safety-enhanced design, which seem critical for security and patient safety. What is the specific rationale for their removal, and what market-based mechanisms or incentives are expected to replace these regulatory safeguards?

It certainly raises eyebrows, doesn’t it? The stated rationale from the office is that these requirements have served their purpose; they are “no longer necessary to advance interoperability” and are not the strong “market driver” they once were for initial adoption. The underlying philosophy here is that the market has matured. A hospital system today would likely never purchase an EHR that lacks robust security features like multi-factor authentication, not because of a government mandate, but because the risk of a data breach is a massive financial and reputational threat. The expectation is that competition will become the new safeguard. If a product is unsafe or insecure, it won’t sell. Developers will be incentivized to build these features not to check a box for regulators, but to win contracts with sophisticated buyers who demand them.

Removing the “model card” requirement for clinical decision support algorithms is a significant change. Without this mandated transparency, how can a hospital system effectively vet an AI model for bias or reliability? Please walk us through the new, proposed due diligence process for a clinician.

This is one of the most significant shifts in the proposal. The Biden-era “model card” was essentially a nutrition label for AI, requiring developers to disclose specific source attributes. By removing it, the rule doesn’t propose a new formal process; instead, it pushes the burden of due diligence entirely onto the healthcare provider. A clinician or hospital IT department can no longer rely on a standardized, government-mandated disclosure. Their new process will have to be far more rigorous and self-directed. It will involve demanding transparency directly from the vendor as part of the contract negotiation, conducting their own independent validation studies, and scrutinizing the vendor’s data on real-world performance. It’s a move from “trust, but verify via regulation” to “don’t trust, and contractually obligate verification.”

The rule plans to alter the definition of “access” and “use” to allow autonomous AI to retrieve and share health data. Could you outline a clinical scenario where this would be beneficial and detail the technical guardrails that would prevent unauthorized data sharing by the AI?

Imagine a patient in post-operative care at home. An autonomous AI could be tasked with monitoring them. This AI could pull real-time data from their wearable sensors, access their EHR for surgical notes, and retrieve new lab results from the hospital’s system the moment they’re available. If the AI’s algorithm detects a combination of factors indicating a high risk of infection, it could autonomously compile a summary and push an alert directly into the workflow of the on-call surgeon. This is immensely beneficial, potentially catching complications hours earlier. As for guardrails, the proposed rule focuses on enabling this data flow, not prescribing the specific technical safeguards. Those would fall to the developers, who would still be bound by HIPAA. The guardrails would likely involve robust API security, cryptographic authentication for the AI agent, and strict, auditable permission scopes that define exactly what data the AI can access and with whom it can share it.

What is your forecast for the certified health IT market over the next three to five years if these changes are implemented?

If this rule is implemented, I predict a period of chaotic innovation. By eliminating 34 of 60 certification requirements and lowering regulatory barriers, the market will likely see a surge of new entrants—smaller, more agile companies focused on AI-driven solutions that couldn’t afford the high cost of legacy certification. We will see a rapid acceleration in creative, AI-enabled tools built on FHIR APIs. However, this also shifts a significant burden onto healthcare organizations to vet these new technologies for safety, security, and efficacy without the guardrails of federal certification. The market will become more dynamic and competitive, but also more of a “buyer beware” environment where the savviest health systems will thrive by picking the best-in-breed tools.