Within the ostensibly sterile and life-saving environments of American hospitals and clinics, a financial model fundamentally at odds with the mission of patient care has taken root, transforming centers of healing into instruments for rapid and often ruthless profit extraction. The escalating influence of private equity in the healthcare sector has introduced a systemic conflict between the long-term needs of patients and communities and the short-term, high-yield demands of investors. This investigation into the operational playbook of private equity reveals a disturbing pattern where cost-cutting measures, debt loading, and asset stripping directly lead to compromised patient safety, diminished quality of care, and in the most tragic cases, preventable death. As these firms quietly acquire hospitals, physician practices, and nursing homes, the devastating human consequences of prioritizing financial engineering over medical ethics are becoming tragically clear.

The Human Toll of Financial Engineering

A View from the Frontlines

The true cost of private equity’s foray into healthcare is most starkly illustrated by the harrowing experiences of frontline medical professionals who witness the degradation of their workplaces. Alfredo Sanchez, a former Army paramedic who transitioned to a role as a trauma ICU nurse at Crozer-Chester Medical Center in Pennsylvania, provides a visceral account of a hospital in its “death throes” under the legacy of PE ownership. He chronicled a persistent and dangerous scarcity of essential resources that became the daily reality for staff. A vital EKG machine with a visibly frayed cord was used until it finally broke down completely, forcing nurses to abandon their critically ill patients to desperately search for a functioning replacement. The ICU routinely ran out of fundamental supplies, such as canisters for collecting bodily fluids and suction tubes required to maintain clear airways for intubated patients. Sanchez described having to “scavenge” for these items from other parts of the hospital, a task that diverted precious time and attention away from direct patient care and underscored the systemic breakdown of the supply chain.

The erosion of standards extended far beyond equipment and disposable supplies, seeping into every aspect of the hospital’s operations and creating an environment Sanchez described as a “war zone.” Critical understaffing became the norm after budgets were “cut to the bone,” placing an unbearable burden on the remaining clinicians. Sanchez witnessed a single nurse being forced to manage the care of three critically ill patients simultaneously, an unsafe and unsustainable ratio that put everyone at risk. The consequences of these cuts were felt acutely when a crucial medication needed to prevent a stroke was unavailable on multiple floors, a direct result of the pharmacy staff being reduced from a team of three to a single individual. Adding to the hazardous conditions, the hospital’s water machine was so widely known to be contaminated with bacteria that the entire staff understood it was unusable, a shocking symbol of neglect in an institution dedicated to health and hygiene. For Sanchez and his colleagues, the daily struggle was no longer just against disease and injury, but also against a system actively undermining their ability to provide safe and effective care.

Systemic Failures, Tragic Outcomes

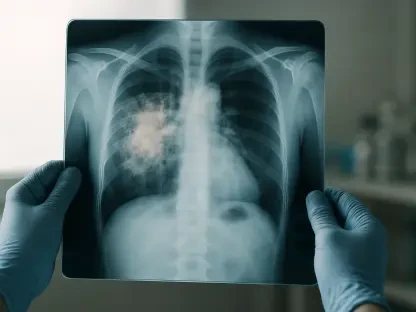

The dire situations described by clinicians like Sanchez are not isolated incidents but rather predictable outcomes of a business model that treats healthcare as a commodity. At St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Massachusetts, then owned by PE firm Steward Health Care, the consequences of this financial model turned fatal. A new mother tragically died from internal bleeding because the embolism coils that could have saved her life had been repossessed by a vendor due to the hospital’s failure to pay its bills. The institution, stripped of its financial resilience by its corporate owners, was unable to maintain access to the basic, life-saving equipment it needed, leading to a completely preventable death. In another disturbing case, an anonymous nurse testified to the Federal Trade Commission about an understaffed emergency room where a psychiatric patient attacked an elderly woman, gouging out one of her eyes and attempting to take the other before being stopped. When staff pleaded for enhanced security, management rejected the request as “too expensive,” offering instead de-escalation training for nurses and instructing them to rely on maintenance workers for protection—a solution that prioritized the bottom line over the physical safety of patients and staff.

This profit-over-patient ethos inflicts a profound moral injury on physicians who are forced to act against their medical judgment. Dr. Jonathan Jones, an emergency medicine physician in Jackson, Mississippi, experienced this conflict directly while working for a PE-owned staffing company. The company mandated that his hospital accept all patient transfers, a policy driven by the higher likelihood that these patients had private insurance and would thus be more profitable. This protocol led to a catastrophic and avoidable outcome for a stroke patient. The man was transferred to Dr. Jones’s hospital, which lacked a comprehensive stroke center and had only one neurologist who did not work nights or weekends. A properly equipped facility was a mere five miles away, but the profit-driven mandate forbade redirecting the patient. As a result, the man was left on a gurney in a hallway, receiving no appropriate treatment for his time-sensitive condition. Dr. Jones remains haunted by the certainty that this patient suffered lifelong disabilities that could have been completely avoided, a stark illustration of how financial incentives can directly supersede and destroy medical best practices.

The Private Equity Playbook

How a Hospital Becomes a Commodity

To comprehend the systemic nature of these failures, it is essential to understand the financial mechanics of the private equity model, which is fundamentally misaligned with the objectives of healthcare. The strategy is often likened to “house flipping,” where an asset is acquired with the sole intention of a quick resale for maximum profit, typically within a short three-to-seven-year timeframe. This abbreviated ownership horizon incentivizes aggressive, short-term strategies designed to boost immediate profitability, often at the expense of the company’s long-term viability and health. Key to this model is the leveraged buyout, a financial maneuver where the PE firm uses a relatively small amount of its investors’ capital—often just 20 percent—and finances the remaining 80 percent of the purchase price with massive amounts of borrowed money. This strategy allows the firm to acquire large assets with minimal upfront investment, amplifying potential returns.

The most destructive aspect of the leveraged buyout in the healthcare context is where the burden of this newly acquired debt falls. Crucially, the massive loans used to purchase the hospital are not held on the balance sheet of the private equity firm but are instead transferred directly onto the books of the acquired hospital itself. Suddenly, the medical institution is saddled with enormous new loan payments it must service. To meet these new debt obligations, the hospital is forced to make deep cuts to its operational budget, which inevitably means reducing staffing levels, skimping on essential supplies, and eliminating less profitable medical services. The PE firm can then extract value through management fees and other maneuvers before exiting the investment, leaving behind a financially hollowed-out institution that is highly vulnerable to bankruptcy. In the case of Crozer-Chester, the ownership group led by Leonard Green & Partners extracted hundreds of millions of dollars, leaving the hospital system “highly leveraged” and ultimately insolvent.

Stripping Assets for Quick Cash

Beyond loading hospitals with debt, another common tactic for generating quick returns is asset stripping, with the “sale-leaseback” being a particularly favored and damaging maneuver. In this arrangement, the private equity firm sells off the hospital’s most valuable tangible assets—the land and buildings it occupies. The firm immediately pockets the cash proceeds from this sale, providing a substantial and immediate return for its investors. The hospital, however, is then forced to enter into a long-term lease agreement to continue operating in the very facilities it once owned. This strategy accomplishes two things for the PE firm: it generates a massive, one-time cash infusion and transforms a stable asset on the hospital’s books into a recurring, often expensive, liability in the form of monthly rent payments. This further strains the hospital’s already fragile finances, diverting funds that could have been used for patient care or capital improvements toward paying rent to a new landlord.

This extraction of value is not limited to real estate. Private equity owners frequently identify and sell off the most profitable parts of a hospital’s operations, such as outpatient surgery centers, diagnostic imaging facilities, or laboratory services. These profitable ancillary services are unbundled from the main hospital and sold to other investors, leaving the core institution to manage the less profitable and more complex inpatient care. The result is a financially weakened hospital that is less able to cross-subsidize essential but lower-margin services like emergency care or maternity wards. Furthermore, PE firms often charge the hospitals they own exorbitant “management” or “consulting” fees that flow directly back to the firm and its investors, creating another channel to siphon cash out of the healthcare system. This combination of debt, asset sales, and fees systematically drains the financial lifeblood from these critical community institutions, leaving them ill-equipped to fulfill their primary mission of caring for patients.

The Data Behind the Devastation

Quantifying the Harm

The harrowing anecdotes from clinicians are not outliers; they are reflections of a systemic trend confirmed by a growing body of rigorous academic research. This data provides the statistical backbone to the personal stories, revealing a clear and quantifiable pattern of deteriorating care and worse patient outcomes at facilities owned by private equity firms compared to other hospitals. A landmark 2023 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) examined Medicare data and found that after being acquired by private equity, hospitals experienced a 25 percent increase in preventable adverse events. These were not minor issues; the study documented a staggering 38 percent rise in central line bloodstream infections, a dangerous complication often linked to staffing and hygiene protocols, and a doubling of surgical site infections. These statistics translate into real-world harm, indicating that thousands of patients suffered preventable injuries, infections, and complications as a direct result of changes implemented under this ownership model.

The evidence linking private equity ownership to increased mortality rates is even more damning. A 2025 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine discovered that PE acquisition of hospitals was associated with cuts to staffing levels and a corresponding 13 percent increase in deaths in the emergency room, a critical access point for care. The findings are particularly grim in the nursing home sector, which has been a major target for private equity investment. A 2023 paper in The Review of Financial Studies, co-authored by Wharton economist Dr. Atul Gupta, found that PE ownership led to an 11 percent increase in the patient death rate. The researchers calculated that this effect implied approximately 22,500 additional deaths had occurred over their 12-year sample period solely due to this ownership model. The increase in mortality was so large and statistically significant that Dr. Gupta and his team initially assumed it was a data error, spending a considerable amount of time triple-checking their work before accepting the shocking conclusion that their findings were accurate.

A Growing Market Monopoly

The scale of private equity’s expansion into the American healthcare system is vast and has been accelerating at an alarming pace, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of medical care delivery. According to data compiled by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, approximately 488 U.S. hospitals are now owned by private equity firms, a figure that represents more than 22 percent of all for-profit hospitals in the country. The growth in PE control over physician practices has been even more explosive. The number of such practices skyrocketed from just 816 in 2012 to a staggering 5,779 in 2021. This rapid consolidation is occurring across numerous specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, and emergency medicine, often creating regional monopolies that reduce competition and patient choice. The public, for the most part, remains unaware of these behind-the-scenes ownership changes, unable to see “behind the curtain” to understand why their local hospital is suddenly understaffed or their doctor’s office is operating differently.

This widespread market consolidation grants private equity firms immense power to dictate prices, staffing levels, and service offerings, often with little to no transparency or public accountability. As these firms acquire more practices and facilities within a given region, they can leverage their dominant market position to negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurance companies, which ultimately drives up healthcare costs for everyone. However, there are nuances within the industry. Dr. Eileen Appelbaum of the Center for Economic and Policy Research suggests that while there are thousands of PE funds, the majority of the most predatory and harmful behavior is concentrated among the 300 largest firms. For example, a single firm, Apollo Global Management, owns nearly half of all PE-held hospitals in the United States. This concentration suggests that regulatory efforts could be more effective if they were targeted at the specific risky behaviors and highly leveraged financial models employed by these major players, rather than a blanket ban on all private investment in the sector.

A Nascent Push for Reform

Federal and State Responses

As the evidence of widespread harm continues to mount, a growing momentum for legislative and regulatory intervention has begun to build at both the federal and state levels. These initiatives are aimed at curbing the most predatory practices of private equity in healthcare and reintroducing a measure of accountability into the system. At the federal level, Senator Ed Markey has introduced a comprehensive bill designed to address the core problems of the PE model. The proposed legislation would mandate greater transparency in healthcare transactions, restrict the sale of essential assets like hospital real estate through sale-leaseback arrangements, and require private equity firms to establish escrow accounts to cover costs in the event of a hospital or nursing home failure. This last provision would ensure that firms cannot simply walk away from bankrupt facilities, leaving communities and taxpayers to foot the bill. Despite the urgent need for such protections, the bill’s passage is considered highly unlikely in the current political climate, highlighting the significant influence of the financial industry’s lobbying efforts in Washington.

With federal action largely stalled, individual states have increasingly taken the lead, acting as laboratories for policy innovation aimed at protecting patients. Oregon passed a landmark bipartisan bill in 2025 that effectively bans the “corporate practice of medicine” by mandating that licensed healthcare professionals must own a controlling share of any healthcare business. This law is intended to ensure that clinical decisions remain in the hands of clinicians, free from the overriding profit motives of corporate executives. Similarly, Massachusetts enacted a law in 2025 focused on increasing transparency, requiring private equity firms to report healthcare transactions to state regulators and placing new limits on the sale of hospital real estate. California passed laws granting the state attorney general greater power to review and even block healthcare deals that are deemed to threaten public access to care. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania, a state heavily impacted by the collapse of the Crozer system, has a proposed bill that would specifically ban the sale-leaseback of healthcare facilities and empower the attorney general to stop transactions that could jeopardize community health services.

A Path Toward Accountability

The examination of private equity’s impact on healthcare revealed a system where financial incentives had dangerously overshadowed the primary mission of patient care. The evidence, drawn from both the harrowing experiences of clinicians on the front lines and rigorous academic studies, painted a consistent picture of decline. It became clear that the standard private equity playbook—characterized by short-term ownership, leveraged debt, and asset stripping—was fundamentally incompatible with the long-term needs of medical institutions and the communities they served. The documented rise in preventable adverse events, infections, and even patient deaths in facilities after their acquisition by these firms provided a somber testament to the human cost of this model. The legislative responses that began to emerge in states like Oregon and Massachusetts signaled a crucial, if belated, recognition that healthcare could not be treated as just another commodity. These reforms represented the first steps toward building a framework of accountability that sought to realign the priorities of healthcare ownership with the enduring principles of safety, quality, and clinical integrity.