A province known for policy brinkmanship now stood on the verge of testing whether a different balance between public insurance and private delivery could rescue a cherished system from its own inertia, and the implications for wait times, professional recruitment, and intergovernmental politics could not be overstated. Alberta’s government appeared ready to put forward legislation that would authorize a parallel, regulated stream of private care alongside public coverage. Advocates framed it as a pragmatic response to mounting strain rather than an ideological gambit, pointing to Europe’s blended models as proof that universalism and choice could coexist. Opponents warned that such a pivot risked undermining equity and breaching federal rules that bind provinces to a common floor of access. The argument ultimately turned on a simple challenge that had grown impossible to ignore: if a system funded for fairness no longer delivered timely care, the status quo had ceased to be defensible. What came next promised a reckoning with both policy design and national identity.

Why the Status Quo Is Cracking

Canada’s single-payer architecture was long treated less as a policy tool than as a national totem, and that symbolism created a powerful headwind against any experimentation that seemed to dilute a shared civic promise. The idea of one payer, one line, and equal treatment carried a moral clarity that shaped political debate for decades. Yet reverence was a poor substitute for performance. Signs of deterioration piled up: emergency departments operating above safe capacity, cancer planning pushed back weeks, and residents without a family doctor left to cobble together episodic care. These failings did not just test patience; they cut at the core of universality by making access contingent on endurance rather than need. Critics of reform often argued that more money would solve bottlenecks, but the data told a more uncomfortable story about structure, incentives, and labor supply.

Moreover, the cultural prohibition against introducing regulated private delivery shielded a model that had become increasingly brittle. Provinces committed ever-larger shares of program spending to health care and yet struggled to deliver timely services, a mismatch that exposed the limits of central funding alone. The result was a perverse politics of denial: parties defended a symbol even as residents waited months for procedures that peers in mixed systems obtained in weeks. That dissonance fostered a new willingness to consider alternatives that preserved public insurance while opening controlled space for private capital and capacity. The emerging conversation no longer turned on whether reform violated national values, but whether refusing to adapt betrayed them by locking in avoidable delays and poor outcomes. In this light, Alberta’s readiness to test a different configuration looked less like provocation and more like a response to realities that had grown too stark to avoid.

What Alberta Plans to Do

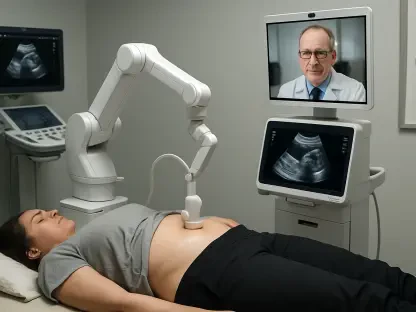

Reports indicated that Alberta’s proposal would establish a parallel private delivery option operating alongside public insurance, with physicians permitted to practice in both realms under clear obligations to serve public patients. The legislation was expected to ban queue-jumping for procedures covered by the public plan, require transparent fee schedules, and attach minimum public service hours to dual practice licenses. In effect, policy architects looked to replicate features common in parts of Europe: free movement of patients within a universal framework, regulated private capacity that added slots without displacing public ones, and strict enforcement against extra-billing that compromised access. The design goal was not to hollow out public provision but to increase total supply, harness investment, and introduce performance pressure through comparison and choice.

Crucially, the approach differentiated between financing and delivery. Public insurance would remain the backbone guaranteeing coverage based on need, while delivery would become more pluralistic to relieve bottlenecks. To make this workable, the province would need to adjust physician compensation models, scheduling protocols, and data reporting so that time spent in the private stream did not erode public throughput. Contracts could include surge commitments during peak periods, rural service credits, and penalties for breaching wait-time targets. Patient protection would hinge on clear billing boundaries and independent audits. Alberta’s advocates cast this as an opportunity to recruit back clinicians who had left for better pay or flexibility, and to attract new providers with modern facilities financed outside the public capital envelope. The wager linked capacity and accountability: expand the number of seats, then measure outcomes and enforce rules.

Money, Capacity, and the Quiet Two-Tier Reality

Budgets told a sobering story. Health care absorbed between 30 and 40 percent of provincial program spending, leaving less room for universities, child care, and infrastructure that also underpinned quality of life and long-term growth. The trajectory threatened to crowd out investments that reduced future health demand, such as housing and preventive services. Even with rising allocations, capacity lagged population needs as demographics shifted and chronic conditions expanded. The conventional fix—injecting more public dollars into the same delivery monopoly—produced diminishing returns. Alberta’s gambit aimed to tap new capital and labor without abandoning universality, recognizing that public coffers alone could no longer fund both renewal and expansion at the required speed. Private delivery under public rules, advocates argued, could modernize facilities faster, scale diagnostics, and shorten queues.

Against this fiscal backdrop, the rhetoric of single-tier access clashed with lived experience. Those with means already bypassed domestic queues by traveling to other provinces or abroad, paying out of pocket for faster surgery or imaging. This under-the-table two-tier reality did not disappear because policy refused to acknowledge it; it simply rewarded those who could afford to look elsewhere. Formalizing a regulated parallel stream inside Canada, with transparent prices and strict equity conditions, could be more egalitarian than an informal market that pushed patients to foreign providers. By accrediting domestic centers under public standards, provinces could keep talent and resources at home, negotiate volume-based pricing, and create space for innovation in scheduling, triage, and care pathways. The tension between ideals and practice thus became a case for honest regulation rather than prohibition that bred inequity through the back door.

The Canada Health Act and the Coming Showdown

The Canada Health Act set the outer bounds of provincial autonomy by conditioning federal transfers on principles that included public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. Alberta’s plan, depending on its details, could test those boundaries. Ottawa had long treated extra-billing and user charges for insured services as breaches that merited clawbacks. A model permitting private delivery for publicly insured services would need to show that access did not depend on ability to pay and that public queues were not lengthened by dual practice. Otherwise, reductions in transfers could follow. Estimates suggested Alberta might risk in the neighborhood of $6 billion in federal health dollars, a sum large enough to trigger both legal arguments and political theater. Whether the federal government punished quickly or exercised discretion would influence not only Alberta’s budget but also the willingness of other provinces to follow.

This confrontation had stakes beyond the ledger. It was, at heart, a test of Canadian federalism’s capacity to act as a lab for policy learning. Provinces had historically piloted reforms—from drug coverage to surgical centers—that later diffused nationally. The worry among reformers was that rigid enforcement of the Act, particularly where rules were open to interpretation, could freeze experimentation precisely when strain demanded it. Supporters of strict compliance countered that allowing private delivery to creep into insured services threatened to erode a shared national promise. The balance would turn on evidence: if Alberta’s rules preserved universal access while improving timeliness, pressure would mount for Ottawa to accommodate. If the experiment produced visible inequities or siphoned staff, the case for penalties would strengthen. Either way, the political clash promised to shape the narrative of what counted as faithful execution of the Act’s principles.

Guardrails, Metrics, and National Stakes

Equity was the hinge that determined whether reform enhanced or undermined the public good. Guardrails needed to be concrete, enforceable, and transparent. Dual practice could not become an exit ramp from public obligations; it had to be a supplement tied to measurable contributions. Mandatory minimums for public service hours, enforced with audits and sanctions, would be critical. Billing frameworks had to draw hard lines between insured and uninsured services, with zero tolerance for balance billing that discouraged lower-income patients. Rural protections mattered as well: incentives to attract providers to underserved regions, telehealth support, and mobile clinics could offset the risk of private facilities clustering in cities. A public registry tracking provider time allocation, wait times, and patient outcomes would convert rhetoric about fairness into observable data. Without such infrastructure, promises of equity would ring hollow.

Metrics defined success. Wait times for surgeries, imaging, and specialist consults would have to fall across income groups and geographies. Recruitment and retention of clinicians, especially in hard-to-staff specialties, needed to improve measurably. Outcomes such as complication rates and readmissions had to remain at least as strong in public settings, ensuring that private growth did not cannibalize quality. Patient satisfaction data, collected independently and stratified by socioeconomic status, would reveal whether reforms expanded choice or simply created a premium lane. Fiscal effects also warranted scrutiny: did private investment reduce pressure on public capital budgets, or did total system costs balloon without corresponding value? Alberta’s performance on these indicators would not only validate or indict its approach; it would set a reference point for other provinces weighing similar moves, turning provincial innovation into a national learning exercise.

Paths Forward And Practical Tests

The most productive next steps were framed around building proof rather than declaring victory. A sequenced rollout with pilot regions allowed rules to be tuned before province-wide expansion, and independent evaluation units could publish quarterly dashboards covering wait times, staffing flows, and equity indicators. Contracting templates that bundled volume targets with penalties for missed public commitments gave administrators leverage to keep capacity balanced. At the same time, targeted training seats, expedited licensing for internationally educated clinicians, and streamlined procurement for diagnostics expanded the workforce and equipment base so that private growth did not drain the public pool. Coordination with neighboring provinces on physician mobility and reciprocal billing prevented unintended cost-shifting. These operational moves were pragmatic and testable; they sidestepped ideological trench warfare by asking whether specific designs delivered measurable gains.

In parallel, intergovernmental diplomacy had been essential. Alberta opened channels for technical briefings with federal officials and other provinces, seeking clarity on how Ottawa interpreted accessibility under the Act and where negotiated exemptions or conditional approvals could be crafted. Transparent risk-sharing agreements, including escrow mechanisms for potential transfer reductions, insulated core services from fiscal shocks while legal questions were resolved. Public reporting, verified by an arm’s-length auditor, built credibility that reforms kept universality intact. If the experiment generated shorter waits without widening gaps, momentum tended to shift toward replication rather than rebuke. If harms surfaced, sunset clauses and course-correction triggers allowed recalibration without abandoning change altogether. By anchoring the debate in results and reversible steps, the path forward emphasized learning over posture, and that approach offered a way out of a stalemate that had defined health policy for too long.