The global map of Parkinson’s disease is rapidly being redrawn, yet the landscape of the research dedicated to conquering it remains stubbornly fixed. A profound and widening disparity now exists between the populations most affected by this neurodegenerative condition and the focus of scientific inquiry. While the prevalence of Parkinson’s is surging in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the vast majority of research initiatives, clinical trials, and funding remains concentrated in high-income nations. This imbalance is more than a statistical curiosity; it represents a critical flaw in the global strategy against the disease, one that systemically excludes millions, hampers a comprehensive understanding of Parkinson’s, and perpetuates deep-seated inequities in healthcare. The current trajectory not only limits the applicability of research findings but also stalls the development of treatments that could benefit everyone, regardless of their geography or background.

The Growing Disparity and Its Consequences

A Widening Chasm in Research Focus

The current framework for Parkinson’s disease research inadvertently sidelines the very populations it must include to achieve a complete understanding of the condition. Today, individuals in LMICs constitute approximately 44% of the global Parkinson’s population, a figure that continues to climb. Despite this demographic reality, these communities, alongside other historically underrepresented groups such as ethnic minorities, women, and those in rural areas with limited research infrastructure, are largely absent from major scientific studies. This exclusion creates a critical gap, as findings derived from a narrow, homogeneous population may not be generalizable to the diverse global community affected by the disease. This lack of representation directly undermines the development of universally effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies, leaving a significant portion of the world’s patients with treatments that may be ill-suited to their unique genetic, environmental, and clinical profiles.

This deficit in diversity has led to significant deficiencies in fundamental scientific knowledge about Parkinson’s disease. Without comprehensive data from varied ancestral backgrounds and diverse environmental settings, researchers are severely limited in their ability to identify unique risk factors, potential protective mechanisms, and the different ways the disease manifests across populations. Key questions regarding the epidemiology of Parkinson’s, its environmental triggers, and its genetic underpinnings on a global scale remain largely unanswered. For instance, exposure to certain pesticides is a known risk factor, but its impact may differ significantly in agricultural communities in Asia or Africa compared to those in North America. This incomplete picture restricts our basic understanding of the disease’s pathology and severely impedes the innovation required to create next-generation therapies that are effective for all.

Systemic Failures and Perpetuating Inequity

The knowledge gap extends far beyond epidemiological data, creating a void in our understanding of the disease’s biological underpinnings. A lack of deep phenotyping and biomarker identification in underrepresented groups means that the global portrait of Parkinson’s biology is dangerously incomplete. This problem is compounded by systemic failures within the research ecosystem itself, including the technical inability to effectively integrate disparate datasets and a notable absence of “diversity-aware analytics.” Such methodological shortcomings prevent researchers from drawing robust, meaningful conclusions even from the limited diverse data that currently exists. Without the tools to properly analyze and interpret information from different populations, the scientific community is left with a fragmented and biased view of the disease, which in turn stifles progress toward discovering universally applicable biomarkers for early diagnosis and disease monitoring.

Ultimately, this profound imbalance creates a self-perpetuating cycle of inequity that has far-reaching consequences. When research is overwhelmingly prioritized in affluent populations, the resulting scientific breakthroughs and advanced treatments primarily benefit those same communities. This dynamic further marginalizes populations in LMICs, who are in desperate need of effective and, crucially, accessible interventions. The result is a stalled progress in basic science, as researchers miss opportunities to study the disease in diverse contexts, and limited success in clinical trials, which often fail to recruit representative cohorts. This cycle reinforces a global healthcare system that is ill-equipped to serve a growing and diverse patient population, deepening health disparities and failing to deliver on the promise of equitable medical advancement for all who live with Parkinson’s disease.

A Blueprint for Inclusive and Ethical Research

Empowering Communities and Adapting Methods

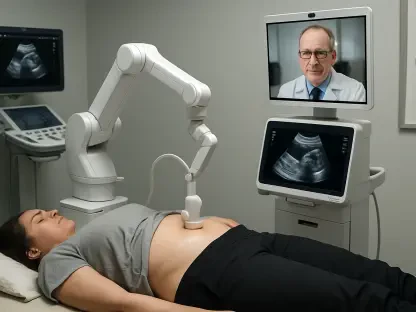

To effectively bridge this research gap, a strategic and ethically grounded agenda is required, one that prioritizes the empowerment of underrepresented communities. A foundational step is to significantly increase and strategically direct research funding toward LMICs. This investment must transcend the traditional model of simply conducting studies in these regions. Instead, it must be channeled toward empowering local institutions, training local scientists, and cultivating sustainable research capacities. By building a long-term foundation for scientific advancement within these communities, this approach fosters local ownership of health solutions and ensures that research is driven by the specific needs and priorities of the populations it aims to serve. Such empowerment creates a more equitable partnership in the global fight against Parkinson’s disease.

Equally critical is the development and implementation of research methodologies that are both contextually adaptable and harmonized for global application. Research tools, protocols, and assessment measures must be thoughtfully tailored to the unique cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic landscapes of diverse populations. This ensures that data collection is not only scientifically rigorous but also respectful of local customs and values. Central to this process is the establishment of sustained, trusting relationships with local communities. Researchers must practice genuine cultural competence, demonstrating a deep understanding of the contexts, beliefs, and needs of the people they study. When community members feel valued and respected as partners in the research process, their willingness to participate increases, leading to richer, more meaningful data and invaluable insights into the lived experience of Parkinson’s.

Reforming the System and Integrating Care

While grassroots efforts are essential, they are insufficient on their own; broad collaboration and systemic reform are imperative for lasting change. The creation of robust, cross-border research networks is a critical component, as these networks can pool resources, share expertise, and unite diverse stakeholders, including academics, healthcare providers, patient advocacy groups, and community leaders. However, a significant barrier remains within the institutional standards of the research world. Many academic journals and funding bodies have policies that inherently favor studies conducted in high-income countries. To genuinely close the diversity gap, these institutions must reform their policies to actively prioritize the publication and funding of high-quality research from and about underrepresented populations, thereby amplifying voices from all regions and ensuring the scientific discourse reflects the true global experience of Parkinson’s.

The path forward was illuminated by a vision that tightly integrated research with clinical care. As scientific inquiry became more globally robust, it was paralleled by a worldwide commitment to establishing and maintaining minimum standards of care and ensuring equitable access to treatments. This comprehensive approach ensured that scientific discoveries translated into tangible improvements in the quality of life for patients across all demographics, reinforcing the value of research and building public trust. Through evidence-driven initiatives and targeted educational campaigns in LMICs, awareness was raised, stigma was reduced, and a more research-conducive environment was fostered. By positioning Parkinson’s as a global health priority, stakeholders successfully championed an inclusive and equitable approach that transformed lives.