The journey to create a new medicine has long been a monumental undertaking, characterized by staggering costs, decade-long timelines, and a frustratingly high rate of failure. For several decades, the pharmaceutical industry has relied on Target-Based Drug Discovery (TBDD), a seemingly logical strategy of identifying a single faulty protein in a disease and designing a molecule to fix it. This approach, once hailed as a revolution, has now reached a point of diminishing returns, where massive investments no longer guarantee breakthroughs. The industry is now standing at a critical inflection point, as the limitations of this reductionist model have become undeniable. Emerging from this period of stagnation is a powerful new force: artificial intelligence. AI is not merely an incremental improvement but a disruptive engine driving the next great leap in productivity, fundamentally reshaping the philosophy and practice of how we discover life-saving therapies.

The Rise and Plateau of a Dominant Strategy

Following the breakthroughs in genomics and recombinant technologies in the latter half of the 20th century, the pharmaceutical world underwent a seismic shift towards TBDD. For the first time, scientists could isolate specific genes and proteins implicated in a disease and then systematically screen vast chemical libraries to find compounds that interacted with these precise molecular targets. The sequencing of the human genome further fueled this excitement, unveiling what seemed to be an endless catalog of potential targets. This method was a departure from older, more observational phenotypic screening and appeared far more rational and efficient. Its initial dominance was solidified by regulatory successes, with a significant majority of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2013 originating from target-based approaches. This period represented the steep, rapid growth phase of TBDD’s S-curve, where the technology delivered tangible progress and became the undisputed industry standard.

However, despite its widespread adoption and early victories, a troubling paradox began to surface: the industry’s overall productivity began to stagnate, and in some cases decline, precisely during the era of TBDD’s dominance. The promise that a wealth of genomic targets would translate into a steady stream of new medicines failed to materialize consistently. A sobering systematic review of thousands of studies revealed that only a small fraction of approved small-molecule drugs were the result of a pure, single-target discovery process. More tellingly, many successful drugs initially believed to be highly specific were later found to owe their therapeutic efficacy to complex off-target mechanisms, a finding that directly challenged the core premise of single-target precision. By the mid-2000s, seasoned experts began to argue that TBDD had entered the obsolescence phase of its lifecycle, characterized by diminishing returns where increased effort yielded fewer breakthroughs. The industry’s near-total pivot to TBDD was, in retrospect, a high-stakes bet that had only partially succeeded.

Unpacking the Core Challenges of the Old Model

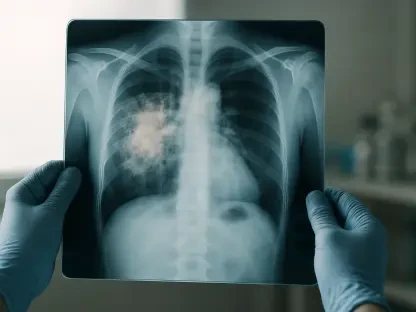

The most formidable obstacle that has plagued TBDD is the challenge of target validation, often referred to as the “valley of death.” This is the cavernous gap between showing that a molecule can modulate a target in a laboratory setting and proving that this action will have the desired therapeutic effect in a complex human being. This challenge is rooted in a fundamentally reductionist view of biology, which presumes that complex conditions like cancer or neurodegeneration can be treated by fixing a single faulty component. In reality, most diseases arise from disruptions across intricate biological networks. By focusing on optimizing a molecule for a single target, researchers have often inadvertently designed out the beneficial multi-target effects that can lead to true therapeutic breakthroughs, contributing to the high rate of clinical trial failures after immense investment in time and resources.

This validation problem is significantly exacerbated by a heavy reliance on preclinical models that often fail to accurately recapitulate human physiology. While essential, recombinant systems, cell-based assays, and animal models introduce layers of uncertainty, as a target that appears promising in these simplified environments may behave differently or prove to be irrelevant within the complexity of a human patient. Furthermore, human bias has played a substantial and often overlooked role in limiting innovation. Research institutions and pharmaceutical companies have historically tended to focus on the same well-studied families of targets, creating an echo chamber that discourages exploration of novel biological pathways. This leads to repeated downstream failures and an inefficient allocation of resources. These factors combine to create a high-risk environment where both “validation risk”—the uncertainty about a target’s biological role—and “technical risk”—the practical difficulty of creating a safe and effective drug—remain perilously high throughout the development process.

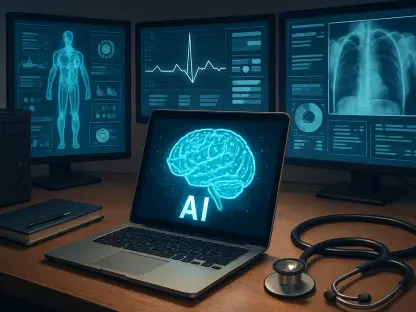

The Dawn of an AI-Powered S-Curve

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are now catalyzing the start of a third S-curve in drug discovery productivity, offering a powerful antidote to the limitations of the previous era. One of AI’s most profound impacts is its ability to overcome the inherent biases that have constrained human-led discovery. By systematically analyzing vast and complex multiomics datasets from patients, AI algorithms can identify patterns and connections that are invisible to the human eye. This allows the data itself to point researchers toward the most relevant biological targets—or, more accurately, the right combination of targets—and the molecules most likely to succeed. This data-driven approach moves discovery away from well-trodden paths and opens up a much wider and more promising search space, enabling the exploration of novel biology with greater confidence.

Beyond its analytical power, AI functions as a dramatic accelerator for the entire discovery and optimization pipeline. Traditional medicinal chemistry is a slow, painstaking, and intuition-heavy process of iterative design and testing. In stark contrast, AI-driven platforms can perform virtual screenings of libraries containing billions or even trillions of chemical compounds in a remarkably short time. Using techniques like deep learning for molecular docking and active learning, these AI models continuously improve with each cycle, rapidly prioritizing the most promising candidates for synthesis and experimental validation. The ultimate transformative power of AI lies in its capacity to integrate disparate data streams. By weaving together patient-derived genetics, network-based biological models, and structure-based design principles, AI creates rapid, iterative feedback loops that de-risk the entire process. This allows for the early identification of targets that are not only genetically implicated in a disease but are also structurally “druggable,” tackling both biological and technical risk at the very outset of a project.

A New Philosophy for a New Era

The integration of these powerful computational tools precipitated more than just a technological upgrade; it demanded a fundamental evolution in the philosophy of drug discovery. The prevailing mindset of searching for a single “magic bullet” for a single target was recognized as insufficient for tackling the complexities of human disease. The new paradigm, enabled by AI, embraced a more holistic, systems-level understanding. Researchers could now identify “context-specific vulnerabilities” within entire cellular networks rather than focusing on individual proteins. This shift allowed for a more nuanced approach to developing therapies that could address the underlying biological system, leading to treatments with potentially greater efficacy and durability. The industry acknowledged that a multi-target pharmacology was not a flaw to be engineered out, but often a key to therapeutic success.

Ultimately, the future of creating new medicines was forged through a synergistic hybrid approach that leveraged the strengths of every major discovery wave. The observational power of phenotypic screening, the precision of target-based methods, and the expansive, data-driven capabilities of AI were no longer seen as competing strategies but as complementary tools in a more robust and adaptable toolkit. This new era of innovation was also defined by a vibrant, collaborative ecosystem where academia, large pharmaceutical companies, and agile “techbio” startups worked in concert. This collaborative model allowed foundational research to be translated into life-saving medicines more efficiently than ever before. Simultaneously, the development of new therapeutic modalities, such as targeted protein degradation and advanced cyclic peptides, expanded the definition of what was “druggable,” opening up entirely new avenues to treat diseases that were once considered intractable.