Australia’s hospital emergency departments are contending with a relentless tide of patient demand that has pushed them to a critical breaking point, where long waits for care have become a dangerous new normal. In this high-pressure environment, a suite of alternative care services has been established to offer a vital release valve, aiming to treat patients with urgent but non-life-threatening conditions outside the hospital walls. While these telephone advice lines, urgent care clinics, and virtual emergency departments each demonstrate considerable promise in their own right, their true capacity to transform the healthcare landscape and alleviate systemic strain depends not on their individual performance, but on their ability to function as a single, intelligently integrated network. Without a cohesive strategy, these solutions risk remaining a patchwork of well-intentioned but disconnected efforts rather than the foundation of a resilient and efficient urgent care system.

Understanding the Landscape

The Overcrowding Crisis

The strain on the nation’s hospital system is not a temporary issue but a rapidly escalating crisis with profound implications for patient safety and care quality. Projections indicate a significant surge in emergency department presentations, expected to reach 9.1 million annually, a stark increase from the 7.4 million recorded a decade ago. This relentless influx has created a severe bottleneck within hospitals, leading to alarming delays at every stage of the patient journey. Current data reveals that approximately one in ten patients requiring an inpatient bed now endures a wait of 19 hours or more in the emergency department, a staggering six-hour increase from just four years prior. Even those who are ultimately discharged home face prolonged waits, with 10% waiting eight hours or longer. These statistics underscore a fundamental challenge that cannot be solved by simply adding more hospital beds. An effective response must be two-pronged: improving the efficiency of patient flow from the emergency department to inpatient wards while simultaneously implementing robust strategies to reduce the number of initial presentations for conditions that can be safely and effectively managed elsewhere.

The persistent gridlock in emergency departments points to a complex interplay of factors that extend far beyond the hospital’s front door, highlighting systemic weaknesses in primary and community care access. When patients cannot secure a timely appointment with their general practitioner or lack access to after-hours services, the emergency department often becomes the provider of last resort, regardless of the severity of their condition. This phenomenon, known as “inappropriate presentation,” contributes significantly to overcrowding, consuming valuable resources and diverting the attention of specialized emergency staff from critically ill patients. Consequently, addressing the root causes of ED overcrowding requires a holistic view that acknowledges the interconnectedness of the entire healthcare ecosystem. The challenge is not merely to manage the surge but to fundamentally reshape how urgent care is delivered, creating accessible, reliable, and efficient alternatives that build public trust and provide a clear pathway for patients to receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time, thereby preserving the emergency department’s crucial role for true emergencies.

Emerging Alternatives to the ED

In direct response to the escalating pressure on hospitals, a multi-faceted strategy has emerged, centered on the development of three distinct but complementary services designed to serve as viable alternatives to a traditional emergency department visit. The longest-standing of these is the Healthdirect telephone service, a national 24/7 hotline staffed by registered nurses. Operational for nearly two decades, this service provides immediate health advice and triage, guiding callers toward the most appropriate level of care, which could range from self-management at home to a visit with a general practitioner or, when necessary, the emergency department. Its primary function is to act as a first point of contact, offering reassurance and professional guidance to help people navigate the complexities of the healthcare system without defaulting to a hospital visit. This service provides an essential layer of support, particularly for after-hours concerns when primary care options are limited, empowering individuals to make informed decisions about their health needs from the comfort of their homes.

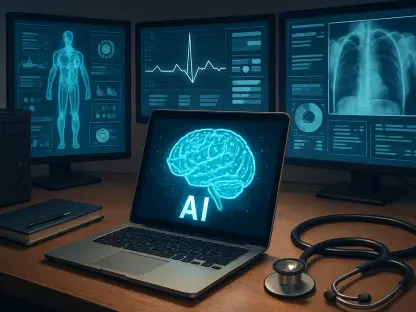

More recently, the healthcare landscape has been enhanced by two innovative models: Urgent Care Clinics (UCCs) and Virtual Emergency Departments. The network of approximately 90 UCCs, heavily promoted by the federal government, operates as a crucial intermediary between general practice and the hospital. Staffed primarily by GPs, these walk-in clinics are designed to manage urgent but non-life-threatening conditions, such as minor fractures, infections, and wounds. Their key advantage lies in their accessibility, offering extended hours seven days a week and providing on-site diagnostic capabilities like X-rays and blood tests, which are typically unavailable in a standard GP office. Complementing this physical infrastructure are the Virtual Emergency Departments, a technological innovation established in several states over the past five years. These services connect patients or other healthcare providers with specialist ED physicians and clinicians via video link, offering expert consultation and triage remotely. This model not only provides direct-to-consumer care but also serves as a vital resource for paramedics and rural practitioners seeking specialist advice, helping to ensure patients are directed to the most appropriate care setting from the outset.

Assessing the Effectiveness

The Evidence Gap

Despite the widespread implementation and public investment in these alternative care models, a significant overarching challenge remains: a critical lack of published, robust evidence comprehensively evaluating their quality, safety, and system-wide impact. While major evaluations of both Urgent Care Clinics and virtual EDs are reportedly underway, the detailed data necessary for evidence-based policymaking and service refinement is not yet publicly available. For instance, an interim evaluation of the UCC network offered no concrete data on safety and quality metrics, noting only that foundational clinical assessments had been conducted prior to their launch. This information gap creates uncertainty about the long-term viability and clinical effectiveness of these services, making it difficult to definitively measure their return on investment or compare their performance against traditional care models. Without this rigorous analysis, health planners and policymakers are operating with limited insight, relying on preliminary data and anecdotal evidence to guide the expansion of programs that represent a substantial allocation of public health funds.

However, some preliminary data points have begun to surface, offering an early glimpse into the potential efficacy of these new models. A notable study from New Zealand on a virtual ED service provided an encouraging benchmark for care quality. The research found that the seven-day re-presentation rates for patients seen through the virtual service were similar to those for patients treated in a traditional, physical emergency department. This finding is significant because re-presentation rates are a key indicator of the quality and completeness of the initial consultation; comparable rates suggest that the virtual model is not leading to a higher incidence of unresolved issues or premature discharges requiring follow-up care. While this single study from a different healthcare system cannot be directly extrapolated, it provides a valuable proof of concept, suggesting that virtual consultations can achieve a standard of care on par with in-person visits for appropriate patient cohorts. It underscores the urgent need for similar, large-scale studies within the Australian context to validate these findings and build a solid evidence base to inform the future development and integration of these critical services.

Current Performance Metrics

The available data, though incomplete, offers a promising yet varied assessment of how effectively these alternative services are alleviating pressure on hospitals. Urgent Care Clinics, in particular, have demonstrated a tangible impact according to an early evaluation. The findings revealed that a substantial 46% of patients who visited a UCC would have otherwise presented at an emergency department. Furthermore, the data showed that only 5% of patients treated at a UCC were subsequently referred to a hospital ED for further care. This suggests that for every ten potential ED presentations from their patient pool, UCCs successfully and definitively diverted approximately four, representing a significant reduction in avoidable hospital visits. This not only frees up emergency department resources for more critical cases but also translates into a modest but important reduction in overall health service costs, affirming the model’s potential as an efficient and effective component of the urgent care ecosystem.

In contrast, the performance metrics for virtual EDs and the Healthdirect telephone line present a more complex picture. Data from services in Queensland and Victoria indicate that around 30% of patients who utilize a virtual ED are ultimately referred to a physical emergency department. This higher referral rate, when compared to that of UCCs, is interpreted as evidence that virtual EDs are managing a patient cohort with more serious or clinically complex conditions that are more likely to require in-person assessment or hospital-based interventions. An economic evaluation of a Victorian virtual ED projected small cost savings, though it was based on a conservative model, with different scenarios suggesting the potential for more substantial financial benefits. The impact of Healthdirect, meanwhile, appears to be mixed. While one review credited the service with achieving “modest but significant” reductions in ED usage, other data highlights a potential gap between advice and action, showing that a high percentage of callers still attended an ED or consulted a doctor even after being advised to do so, a discrepancy that warrants further investigation to optimize its effectiveness.

Building a Cohesive System

Optimizing Individual Services

To realize the full potential of a networked urgent care system, each component service must first be optimized to perform its intended function with maximum efficiency. A critical insight from the evaluation of Urgent Care Clinics revealed that half of all their patients stated they would have visited their regular GP if an appointment had been available. This finding suggests that a significant portion of the UCC workload is currently being driven by broader issues of primary care accessibility rather than a specific need for urgent care. Consequently, improving general access to GP services could free up considerable capacity within UCCs, allowing them to concentrate more exclusively on their core mission: treating patients at a higher risk of presenting to an emergency department. Refining the role of UCCs to better target this specific demographic would not only enhance their impact on hospital avoidance but also ensure that public health resources are allocated more effectively, strengthening both primary and urgent care tiers simultaneously.

Similarly, there is significant untapped potential in scaling up virtual ED services, which, with some exceptions, currently operate on a relatively small scale. The Victorian virtual ED, which handles over 700 calls daily, serves as a powerful example of what is achievable through large-scale implementation. Expanding smaller, state-based virtual EDs to a similar capacity would dramatically increase patient access to specialist emergency advice, particularly for those in rural and remote areas. Moreover, such an expansion would likely generate significant economies of scale, driving down the average cost per consultation and making the service a more financially sustainable public investment in the long term. As the volume of consultations increases, the fixed costs of technology, infrastructure, and administrative support are distributed over a larger base, improving overall efficiency. A strategic effort to scale these services is therefore not just about extending their reach; it is about fundamentally enhancing their value proposition as a cost-effective and indispensable pillar of a modern, integrated healthcare system.

The Power of a Networked Approach

The ultimate transformation of urgent care delivery depended not on refining these services in isolation, but on weaving them into a single, collaborative system where information and patients could move seamlessly between them. The vision was for a future where a virtual ED physician, after assessing a patient remotely, could directly book them an appointment at a local UCC for a necessary blood test or X-ray, bypassing the hospital entirely. In another scenario, a GP at a UCC facing a complex case could initiate an immediate video consultation with a virtual ED specialist for expert advice, enhancing the quality of care on-site. These examples illustrated a networked approach that leveraged the unique strengths of each service to create a patient journey that was more efficient, convenient, and clinically appropriate. The development of such linkages, however, was not a simple administrative task; it required dedicated research to design effective protocols, establish clear clinical governance, and implement shared technology platforms to ensure seamless communication and coordination.

In the end, the journey to alleviate hospital overcrowding revealed that Australia’s three main ED-alternative services had been evolving largely independently of one another. To truly revolutionize urgent care, a comprehensive and deliberate plan for their integrated development, implementation, and evaluation proved necessary. While each service individually contributed to keeping people out of strained hospitals, the analysis made it clear that the collective value of a connected, collaborative system was ultimately far greater than the sum of its individual parts. The path forward involved breaking down the operational silos that separated them, fostering a culture of partnership, and building the technological and clinical bridges needed to create a truly unified urgent care network. It was through this strategic integration that the full potential of these innovative models was finally unlocked, marking a pivotal shift toward a more resilient, patient-centered, and sustainable healthcare future.