Paul Alexander is not a man whose name has been written in the annals of history, but perhaps he should be. At 78, Paul passed away on the 11th of March 2024 after a 72-year battle with polio. Paul Alexander was the longest-living survivor of polio, but having contracted the viral infection in 1952, was confined to life in an iron lung. The first polio vaccine became available just three years later and since then, 2.5 billion children have been vaccinated against the virus in over 200 countries, with the help of 20 million volunteers.

In most developed and developing nations, poliomyelitis has largely been eradicated, and herd immunity achieved. But over the last 20 years, pseudo-science claims that vaccines (specifically for measles, mumps, and rubella) are linked to autism have increased vaccine hesitancy among many communities in the West.

Let’s take a look at how vaccine hesitancy is impacting polio across the globe.

Could Polio Be Making a Comeback?

While many believe that polio has altogether been eradicated, a spate of infections in London, New York, Montreal, and Jerusalem have alerted scientists, epidemiologists, and healthcare workers to the rising prevalence of the virus and the reality of vaccine hesitancy. These countries, previously regarded as polio-free, have raised questions about the polio eradication mission, while experts insist that despite these incidences of resurgence, we’re incredibly close to reaching the goal of a polio-free world.

Immunization rates are steadily declining, thanks in part to COVID-19. Research suggests that parents who refuse to vaccinate their children fall into one or more of four categories:

- Religious beliefs

- Personal beliefs

- Philosophical reasons

- Safety concerns

These concerns have led to small pockets of under-vaccinated groups in developed countries, where vaccines for preventable diseases are readily available. Looking at Europe to gain a better understanding of who these groups might be, research indicates that the following communities show high rates of under-vaccination:

- Orthodox Protestants

- Anthroposophists

- Roma

- Irish Travelers

- Orthodox Jews

While these groups may be in the minority, the risk they pose is quite significant. In 2004, a rubella outbreak in an under-vaccinated group (religiously affiliated) in the Netherlands spread to Canada and resulted in congenital rubella syndrome. In a separate 2008 study, the “spillover” effect that unvaccinated communities have on the general population was observed. In Germany, a measles outbreak occurred, originating from the Anthroposophic community to a portion of the population with lower-than-recommended vaccine coverage (i.e. herd immunity wasn’t achieved). In a third instance, also in the Netherlands, a measles outbreak that started in the Orthodox Protestant Reformed churches spread to the children of vaccinating parents; the children affected were too young to receive the vaccination.

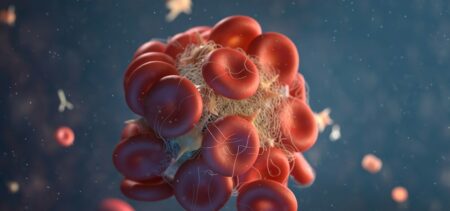

Going back to polio, the issue with missing vaccinations or outright refusing them is the potential resurgence of preventable diseases. In 2022, a strain of the poliovirus WPV1, which has its origins in Pakistan, was detected in children with paralysis in Malawi and Mozambique. As polio hasn’t been eradicated globally, this is a worrying trend, made even more concerning by the fact that those with access to the vaccines are contributing to its spread.

How Did the Poliovirus Return in Developed Countries?

The prevailing theory among groups that choose not to vaccinate is that protection is still available through herd immunity. And in countries like the United Kingdom, the US, Canada, and Israel, where polio has been eradicated for decades, the emergence of the disease has been a reminder that eradication is only possible through ongoing immunization efforts. But the question remains, with high vaccination rates, how could the virus be detected?

The answer, conversely, lies in the vaccines themselves. Vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) is what has been detected among under-vaccinated groups in developed nations. The oral polio vaccines (OPVs) use a weakened form of the virus to help children build immunity. Once a child has received the vaccine, the weakened virus is shed into the environment; ordinarily, this has the effect of providing indirect protection for others. However, in under-vaccinated communities, the weakened virus can circulate, mutate, and ultimately result in paralytic outbreaks.

While great strides have been made in eradicating the wild poliovirus, the variant viruses are prevailing across the globe. As of 2022, there are over 600 cases of VDPV type 2 (cVDPV2); previously only detected in Nigeria, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, this strain has now also made its way to the West. This demonstrates the ability of the poliovirus to spread and rapidly cross borders.

How Do We Tackle This?

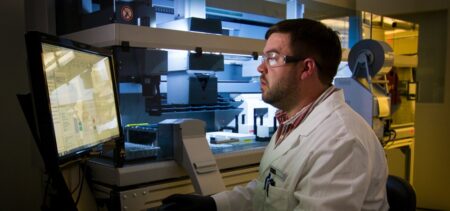

When looking for solutions, experts seek technology to overcome the persistence of vaccine-derived poliovirus. With the issue stemming from oral polio vaccines, scientists are working to create a more genetically stable OPV strain that would be less likely to evolve into a VDPV. Scientists have been working on this from as far back as 2011, exploring the possibilities of a “next generation” vaccine that remains easy to deliver and administer while retaining intestinal mucosal immunity.

While much effort has been made to create new strains of OPVs, the fact remains that high levels of immunization are needed. The biggest risk in vaccine-derived polio is paralysis in infected children. Experts advise that a timely response is necessary when polio is detected in an environmental sample or confirmed in a case of paralytic polio. Guidelines and protocols must be readily available to launch a swift outbreak response campaign in an effort to reach vulnerable communities.

To ensure the ongoing protection of all vulnerable populations, cross-border coordination is key. High-risk neighboring countries have already started implementing this, and we’ve seen successful examples in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Similar efforts have also been made in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. They’re communicating, sharing resources and information, and synchronizing campaigns to ensure all migrant, vulnerable, and underserved communities are reached. This is what needs to happen across all fronts and within all communities around the world.

Combating Vaccine Hesitancy

Simply utilizing government-led campaigns is not enough to convince unvaccinated groups to comply with vaccine mandates; a more grassroots approach is required. Countries in the West can learn a great deal from the African approach to converting the unvaccinated. Where religion is a compelling force for vaccine resistance, religious leaders must be the voice of reason. According to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), Nigerian clerics have been instrumental in spreading the message of vaccination among harder-to-reach populations.

“I used to chase off immunization officers whenever they came to my door because I believed there was a hidden agenda behind it, and I was also uncomfortable allowing my wives to go to the hospital,” said Malam Musa Abubakar, a resident from Zaria, Nigeria. His opinion changed once he was informed by a trusted leader, a Muslim cleric, about the importance of vaccines for his children and access to healthcare for his wives.

Dr. Anis Siddque, the Chief of Communication for Development at UNICEF addressed 228 religious leaders at an annual conference in Abuja, Nigeria, in 2018, gathering support to spread the message of the importance of the polio vaccine and other immunizations. His work, alongside that of thousands of others, has certainly paid off. Sheik Abubakr Gumi, an esteemed Muslim thought leader and cleric, has attested to this, stating that “up until a few years ago, people in Muslim-majority communities stayed away from health centers, rejected polio vaccines and other routine immunizations even if they were brought to their doorstep due to misconceptions, suspicions, and socio-cultural norms. But this changed with the engagement of religious leaders, who have succeeded in mobilizing people against behaviors that have put the lives of women and children at risk.”

Conclusion

Vaccine hesitancy is growing in the global West. With immunization levels falling, vaccine-preventable diseases like polio have a chance of coming back with a vengeance. For those of us born in times cushioned by the safety of immunization, it can be difficult to imagine the great risk that these diseases once posed and the unimaginable suffering of parents and children alike who were infected. But when we think of people like Paul Alexander, who endured an entire lifetime confined to iron lungs, we’re motivated to do more to attain the vision of a polio-free world.

Experts advise working with the religious and socio-cultural leaders of under-vaccinated groups if we are to win the trust and confidence of these communities. Cross-border collaboration for a coordinated response is vital to combating viral outbreaks and stopping the spread quickly and efficiently. Meanwhile, in the background, scientists continue to work on creating new strains of oral polio vaccines, to prevent the development of vaccine-derived poliovirus at its source.

By attacking polio vaccine hesitancy at all levels, we eradicate the disease and prevent any child from being limited by paralysis or confined to a life in an iron lung.