FDA defines drug shortages as the time-limited situations resulting from the drug demand exceeding the drug supply. To qualify as such, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) verifies the drug stock with the manufacturers. However, the state of being medically necessary does not count in listing a drug as being on a shortage, just its demand-supply ratio.

The extremely critical drug shortage situation in the USA recently appeared in some of the most renowned online publications. NY Times and Washington Post both tackled this topic and tried to figure out the in-depth factors involved, as well as list the potential solutions.

Statistically, it appears that the number of drugs included in this category went up by 74% compared with five years ago. This sharp and uninterrupted rise started in 2008, although before that the drug shortages used to be in decline (2001-2007).

Drug shortages: reasons

The most common reasons (almost all related to the manufacturing process) comprise various instances:

- An unpredictable raise in demand (not related to manufacturing, random and reparable with a certain delay);

- Quality-related delays (when products get recalled due to quality issues or have to be replaced at the source);

- Raw materials crisis (when the necessary substances/materials are scarce or lack altogether due to various reasons);

- Financial issues (when companies cease to supply or even to produce certain drugs due to low profits and/or lack of financial incentives that would compensate the situation);

- Infrastructure issues (when elements from the chain of production or supply are lost, as it was the case with older facilities that did no longer comply with modern standards and were also too expensive to bring up to date);

- Business decisions and drug company consolidation decisions that affect established products and contracts insofar as preventing renewals.

- Unknown reasons (mentioned in a study on longitudinal trends in U.S. drug shortages carried on in hospitals’ ER).

The types of medication affected by drug shortages

It is alarming that most of the unavailable drugs are necessary in “direct, life-saving interventions” and sometimes completely lack any substitute.

Some types of medication are “traditionally” prone to shortages, such as generic cancer drugs (e.g. generic chemotherapy agents are vulnerable to shortages since 2006), while other drugs are in short supply in premiere.

These unexpected newcomers count among them the following:

- heart medications

- analgesics

- intravenous electrolytes

- leucovorin

- propofol

- morphine

- hydromorphone

- furosemide

-

amino acids

Resources for coping with drug shortages

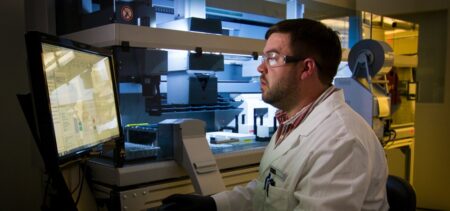

In March 2015 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched its first mobile application in view of this drug shortage situation. Their app identifies and lists all drug shortages, and allows browsing by generic name or active ingredient, as well as by therapeutic category. The updates count on verified reports from the public and on manufacturers’ feedback. The app is available for download in both Google Play and IoS store.

The same agency issued a long-term plan aimed at preventing drug shortages, a Manual of related policies and procedures, a dedicated RSS Feed and an Email notification service. FDA underlines in its infographic on this topic the number of averted shortages, as well as the number of reported shortages.

The American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) also has its own drug shortages related resources, and here one may find out the situation on a certain medication by using the available search feature.

As a medical professional, keeping informed is the best way to go. For more detailed reports on what not being able to use or prescribe a certain drug because of its shortage those interested can check online posts that cover this issue. Even when your first option in what medication is concerned is out of reach, planning ahead is always better than being taken by surprise.

In summary, the situation is critical, as the medical professionals describe it – and they are the most qualified to do so.

Drug shortages: facts

According to the various sources already quoted above, some of the shortage-related facts look like this:

- the average shortage in emergency drugs: nine months;

- the most common shortages: drugs used in treating infections (148), especially antibiotics that fight Clostridium difficile, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), or Pseudomonas aeruginosa;

- a particularly problematic drug shortage: nalaxone, employed in injectable treating opiate overdoses;

- FDA shortage drug reports between 2011 and 2013: 740;

- Side effects due to drug replacement: 27% in chemotherapy, 17% opioid analgesics;

- The drug scarcity puts pressure on medical decisions when rationing guidelines cannot cover real life situations: doctors have to make painful decisions and patients face standards they aren’t even aware off in order to make the priorities’ list.

Drug shortages: impact

The conceptual impact hits the idea of civilized society, top-level services and public welfare. When healthcare professionals alter their decisions due to what is actually available versus what should be at their disposal, the final result implies a series of re-adaptations and shortcuts that should not burden the agenda of an established doctor.

The healthcare system has to cope with a different kind of disaster and therefore employs disaster response procedures, doing their best to “patch together” whatever is left out of the standard procedures and treatment.

The idea of a new normality that includes drug shortages requests adapted strategies. A doctor mentioned how patients actually have to stand military selection procedures – an image that is shocking to conceive in this day and age.

The American Hospital Association issued a letter to the NY Times editor in which it mentioned how all stakeholders, government regulators and drug manufacturers should join the hospitals in taking some of the potential measures that would lead to this crisis’ alleviation, since hospitals cannot address the issues alone. The problem calls for a conjoint reaction and viable solutions, considering how it directly impacts the quality of paramount services, and ultimately modern societal standards.