From March 2016 the first 3D printed drug approved by the FDA is officially available on the U.S. market. Aprecia Pharmaceuticals’ Spritam medication (active ingredient – Levetiracetam), destined for the treatment of partial onset, myoclonic, and primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (various types of epileptic seizures) marks an important landmark in drug manufacturing. Drug printing in its 3D version enters the market.

FDA has previously approved the 3D drug printing for Spritam in view of consumer use in August 2015, in a move considered by some as being 3D drug printing -friendly. Aprecia Pharmaceuticals itself has another three products on the line for 3D drug printing, currently in various early stages, the most developed of them going through formula development.

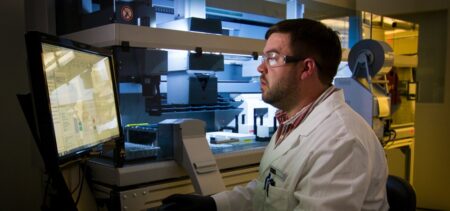

The production technology involved in Spritam tablets’ production, called ZipDose Technology, is a powder-liquid three-dimensional printing or powderbed inkjet, exclusively licensed to Aprecia by ZCorp (a technology originating from MIT), currently part of 3D Systems.

The adjacent progress resides in pill customization, since this new manufacturing process is able to fulfill the one-size-fits-all standard and allows the pills to fit the patients’ body weight and specific dosage.

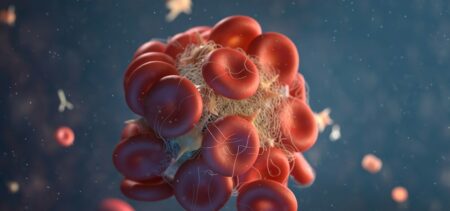

Administering the medication is also easier with the 3D-printed pills since they dissolve in the mouth with the help of a small amount of water; the 3D printing works by repeatedly spraying the layers of powder one on top of the other, instead of using compression or molding techniques, therefore the ease of disintegration when administered. This makes the pills what is called “fast-melt” or more porous in comparison with the classically manufactured pills.

3D drug printing and the expected changes

Before the March 2016 moment the topic of 3D-printed medication issued quite a long analysis and debate by various online and offline sources.

The main improvements expected from this new kind of manufacturing process would be (we have also included some dilemmas):

- Personalized drugs, from the manufacturing stage (taking into consideration personalized prescriptions, based on age, race, gender, the unique individual response to medication and so on);

- A wider array of dosage forms (linking to the above characteristic and to the ease of adapting the manufacturing settings in order to produce different dosage pills by using basically the same production “line”);

- Improved and considerably more complex drug release profiles: another side of drug personalization that has to do with the way the active substances are broken down and metabolized by each patient; targeted and even controlled drug release is now possible via a binder printed in-between the powder-bed layers, a binder that acts as a barrier and allows controlling the release speed and times;

- The seemingly futuristic living tissue printing, a project whose feasibility lies somewhere around 20 years from now, as the experts see it.

- Various innovations, manifesting in a possible cluster of healthcare-related startups, ranging from treatment and production innovations to technical innovations destined to lower the time and money necessary for further progress;

- More cyber-security concerns (technically not an improvement, unless the cyber protection degree becomes higher), since the healthcare information involved in this new type of medicine would be even a more attractive target for cyber-intruders and their malicious actions, medication blueprints and personal data included.

- Less dosage failures are also envisaged once the medication dosage would be taken over by the 3D printing dedicated software. As a direct consequence of this shift in dosage authorship, the question of possible liability distribution has been raised – who will be responsible in case of an error?

- There was also talk of transitioning from medical prescriptions to medical algorithms that would comprise detailed information on which micro-techniques and dosages to be employed in the 3D printing process.

- Shifting the medication production processes closer to customers could help in dealing with drug shortage issues if the future of medication should prove favorable for 3D drug manufacturing.

- A more far-fetched, yet not impossible future prediction consists of the multiple drugs in one single pill concept, a welcome solution for those patients whose treatments involve various pills in different dosages as part of their daily medication; the British researchers have managed to combine captopril and nifedipine (used in regulating blood pressure) with the glipizide (type 2 diabetes medicine) in an unique pill.

- Another reason of concern consists in the possible application of the 3D drug-printing technology into the narcotics medium, once it will be widespread and more available to access;

3D drug printing – the technology

We mentioned at the beginning of our article the drug printing proprietary technology used by Apreia Pharmaceutical – the ZipDose Printer.

The printer itself is approximately 6 by 12 feet, and lays down disc-shaped amounts of powder through a small nozzle. The layers of powder are imbued with tiny droplets of liquid that contains the drug’s active ingredient, the two components binding at a microscopic level.

Since there is no molding or compression, the resulting pills are taller in size and with a slightly rougher exterior aspect, and their consistency is more porous and prone to instant disintegration when in water. The concentration is nevertheless more powerful (or it can be if desired) since the inert filler material specific to traditionally manufactured pills does not apply in this case.

The medical and architectural industry used ZPrinters before – this inkjet technology refined the color layers printing (its specific application) into simulating the appearance of other types of material – a reason that determined the Z Corp (3D Systems, since 2012) to re-brand the base technology as Color Jet.